Evaluating New Programs Before They Launch: A Simple Approach to Ensuring Program Demand, Quality, and Viability

By Wallace K. Pond, Ph.D.

In my nearly 30 years of experience in higher education, I have participated in the development and roll out of dozens of new academic programs at the associate, bachelor’s and graduate levels. As an accreditation evaluator, I have reviewed many dozens of other programs as well.

One theme that has spanned nearly 30 years of work with academic programs is the frequent absence of a comprehensive review of the underlying viability of programs before they’re actually launched.

In many cases, there is anecdotal evidence about the market demand for a given program (and that perceived demand often turns out to be real), but even when that happens, there has usually been limited, formal evaluation applied to a long list of other factors that comprise “viability.” As a result, it is common to see programs hastily launched based on perceived or real market demand that results in operational problems down the line.

That is unfortunate because new programs are critical to the sustainability of private sector colleges and universities, and, in fact, generally speaking, new programs and new students account for about 30 percent of revenue in any given year. One would think that due to the criticality of new programs that schools would approach new program development with the same focus and accountability that they do with other things such as admissions, retention, career services, clinical education, compliance, etc. Ironically, that is usually not the case and, in fact, new program development is often a remarkably haphazard process in which someone in Academics is assigned the task of putting together a new program accreditation application after someone else in the institution has already decided to launch the new offering.

On the other hand, a great advantage of private sector schools is that they are generally quick to market and curricula are almost always application based, which serves graduates well in terms of employable skills.

However, sometimes being quick to market comes at the expense of due diligence that had it taken place, would have either strengthened programs or resulted in a decision not to launch a program at all.

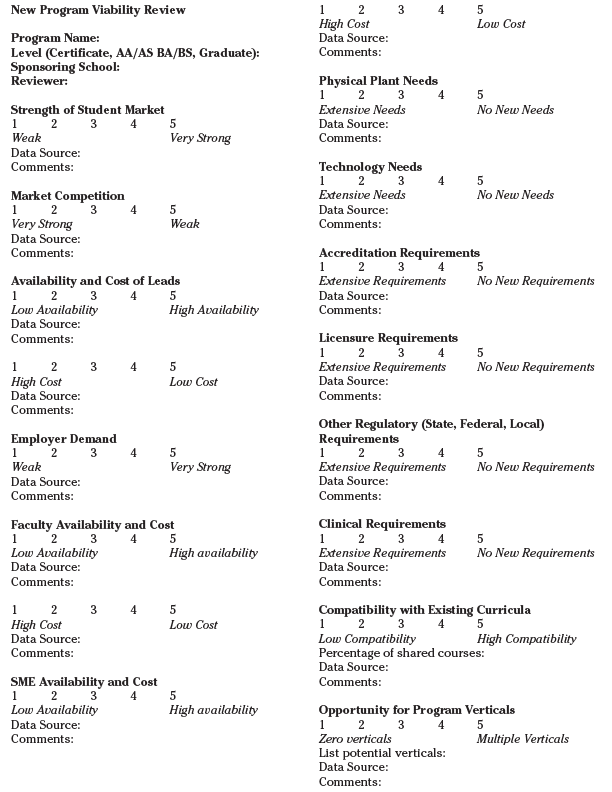

Because I had seen so many programs that lacked a solid vetting process, I eventually developed my own “New Program Viability Review” which I have been using for nearly a decade. It is a comprehensive rubric that covers several basic areas and which requires that items within those areas be individually scored. Although the process does require some modest investment of time and labor, it is quite simple, and ultimately leads to a program viability score. An institution can set whatever minimum score it wants as “minimum viability,” but the higher the score, the more likely it is that the program will be successful. I typically set 50 as a minimum score for consideration. In my experience, the entire review can be completed in two to four weeks in a private sector school if someone is dedicated to the process.

The areas of review include:

- Market and employer demand and competitive landscape

- Availability of faculty and subject matter experts

- Availability and applicability of existing physical plant and technology

- Accreditation, licensure, and regulatory implications

- Compatibility with existing programs

- Incremental delivery costs

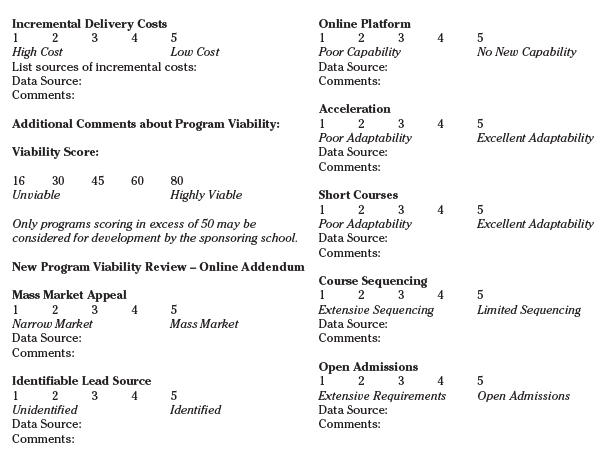

The model also includes an additional, separate rubric for online delivery.

As someone who began his career as a “pure” academic, I tend to see higher education operations through an academic lens, which certainly informs the viability review, but each area of the rubric was chosen based on my operational experience in higher education and the hard-won lessons that come from leaping into new program areas only to learn later than my institution was not fully prepared for effective implementation. In other words, developing a new program application is almost the easy part. Actually creating a new curriculum, then effectively delivering it to students is much more challenging and that speaks to why the viability rubric has the items it does.

Most schools instinctively understand that market and employer demand are baseline requirements for new programs and it’s exceedingly rare for any institution to launch a new program without some sense of the demand. It is less common for schools to confirm that they have or can find adequate and affordable faculty for all new courses or subject matter experts for curriculum development or industry experts for program advisory committees. Institutions eventually put together PACs for new programs, but almost always after the program has been developed and launched. This should happen first, and the PAC should contribute to the development of the curriculum!

It is also important for colleges and universities to carefully assess the needs of new programs relative to physical plant and technology. What can be shared? What will be purely incremental? Moreover, what existing curriculum can be used or adapted for new programs? I have a personal goal of any new program to use at least 30 percent of existing curriculum and the more, the better.

As it relates to accreditation, licensure, and regulatory issues, most schools see this part of the new program process as limited to the required applications and approvals, but it is ideally much more than that.

For example, if a program requires that students pass a licensure exam in order to be employed, it is critical that the process ensures that the curriculum is built from the ground up to support passing the exam, both through course content and through direct exam preparation. Similarly, while programmatic accreditation may be optional from a regulatory perspective, is it really optional from a competitive perspective?

Another key area of the viability review is compatibility with other existing programs as well as program “verticals” (the ability to stack vertical program levels in the same discipline). It is common for schools to launch new programs simply because there is a compelling market opportunity. However, this can be a big mistake even if a new program does provide access to new students. For example, if a new program requires separate, stand-alone labs or technology or faculty that do not exist in any other programs, the cost alone could be a net negative. Moreover, institutions should generally only launch programs that fit their “identity” and mission. I have seen examples such as an allied health school that started a computer programming degree because of the perceived market opportunity. Of course, schools can always expand their program offerings into totally new subjects, but new programs in areas in which you already have the expertise and a good reputation are almost always more likely to be successful and of higher quality than programs in areas that are foreign to the institution.

In short, the New Program Viability Review rubric is a straightforward process for ensuring that key areas of program viability have been evaluated and quantified. The process requires a “project manager” (usually a program director or other academic personnel) who completes the rubric with the assistance of others in the organization. The project manager generally conducts brief interviews or questionnaires with individuals or small groups that have the expertise to evaluate each item on the rubric. In some cases, the score for a given item may have some subjectivity to it, but it is at least based on expert input. In addition to providing a viability score, the process also serves as a framework for the work that has to be done to effectively launch the program if the decision is made to do so – and it is important to remember that there is a difference between assessing the viability of a new program versus actually developing and launching a new curriculum.

A sample rubric is included with this article. It can, of course, be modified for the needs any particular institution or program. There might be items related to international students or clinical education or partnerships etc. that are not in the sample rubric.

You may contact the author for more information about the Program Viability Review process or other higher education issues at: wkpond@comcast.net, www.wallacekpond.com, 719-247-0486.

DR. WALLACE K. POND, for the last 15 years, has been a senior executive in higher education, holding both campus level and corporate positions overseeing large, multi-campus and online institutions of higher education in the U.S. and abroad. He has served as chancellor, president, CEO, and CAO (Chief Academic Officer).

Dr. Pond has been a mission-driven educator for 28 years. He began his career as an adjunct professor and high school teacher and spent six years in the elementary and secondary classroom working primarily with at-risk youth. Wallace was also a public school administrator and spent another six years as a full-time education professor and administrator, working in both on groun campus and online education, bringing education to underserved students. He has also taught as an adjunct instructor at six universities in the U.S. and Europe. Dr. Pond has lived, worked, and studied in North America, Latin America, the Caribbean, Europe and Asia. He has presented nationally and internationally and is the author of numerous articles and the book, “The Lights Are On, Is Anybody Home? Education in America.”

Wallace, a licensed pilot, has a bachelor’s degree in Spanish, a Master’s degree in Human Resource Education, and a Ph.D. in Education. He has two grown children and resides with his wife and youngest daughter in Colorado.

Contact Information: Wallace K. Pond, Ph.D. // 719-247-0486 // wkpond@comcast.net // www.wallacekpond.com