Pricing Strategy

By Bob Atkins, CEO and Founder, Gray Associates

For almost a decade between 2000 and 2010, tuition and fee increases for postsecondary education could be combined with growing enrollment to increase revenue, margin, and profits. In our view, those days are past. Enrollment is declining – and price is part of the problem. Middle class students and their families are strapped. Many are skeptical of taking on more debt. And almost everyone wonders if postsecondary education is worth the cost.

In response, institutions are changing their prices, scholarships, discounts, and programs. Some schools have simply cut tuition substantially – as much as 20 percent for new undergraduates. Many of the largest, publicly held for-profit institutions have frozen tuition and are now offering substantial scholarships (e.g., the Phoenix Reward Scholarship). Some of these pricing initiatives focus on retention. In another approach, schools have restructured programs, making them shorter and less expensive – both of which increase the odds of completion. In another approach, discounts are based on the number of courses completed; often these discounts are structured to make the final phases of a program nearly free.

So far, the jury is out on these initiatives. In general, it is too early to tell, from published reports, whether the price cuts are achieving big enough improvements in starts,retention, or regulatory compliance to justify their costs. However, the investment community is paying attention, with a very recent J.P. Morgan research report stating “we prefer low tuition schools.”

“In general, it is too early to tell, from published reports, whether the price cuts are achieving big enough improvements in starts, retention, or regulatory compliance to justify their costs.”

As a result, price is now an unstable strategic weapon. Even if you leave it alone, it may detonate if students resist your current price, and enrollment and profits fall. If you cut price too much, enrollment may grow, but margins and profits may plummet.

To help you respond to this challenge, the following white paper lays out a way to think about pricing strategy and an approach for determining the right pricing actions for your institution.

Effects of pricing on student demand

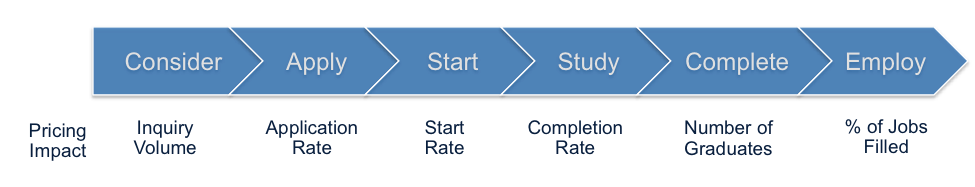

Pricing can affect every stage in the student lifecycle, from consideration through completion. For example, rumors and news about price and college in general may change potential student interest, consideration, and inquiry volumes. Marketing new price points, scholarships, and promotions is now fairly common and may help to stimulate inquiries.

The next point of influence is during the application process. At this point, the school can communicate price and discounts directly, which may influence the probability of applying. Any improvement in application rates would leverage marketing investments made to stimulate inquiry volumes and would flow through to starts, gainful metrics, revenue, margins, and employer demand. However, during the application process, price sensitivity tends to increase as prospective students gain more detailed knowledge of price, grants, loans, and future payments they will have to make.

Changes in any of these elements of pricing may also affect the percentage of applicants who actually start. Small changes in the start ratio would have a significant impact on starts, revenue, margin, and the ability to meet employer demand for graduates.

Once students are in school, the length and cost of the program may affect persistence and completion rates. At this stage, shortening program length and offering persistence-based scholarships may help to increase retention, graduation rates, employment, and gainful employment regulatory outcomes.

The challenge for all of these approaches is that the cost of a price change is relatively clear, certain, and often large; in contrast, the benefits, such as increased enrollment and better gainful employment outcomes, are unproven. The balance of this document suggests a methodology that can enable you to better understand and predict these trade offs. Let’s start with a closer look at the economics of a price change.

Effects of pricing on school economics

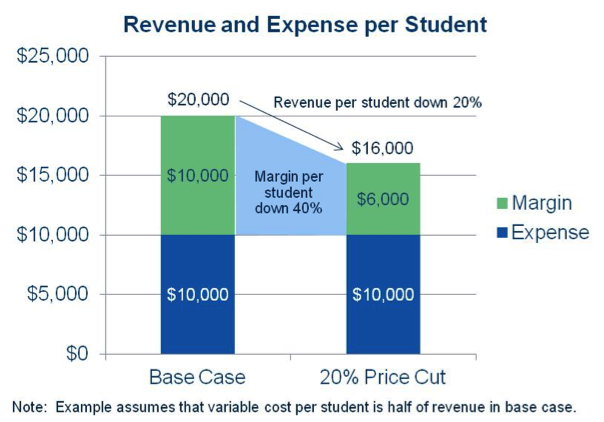

Typically, a price cut directly reduces revenue per student: a 20 percent price reduction will reduce revenue per student by 20 percent. If the price cut is only for new students, then the effect will be much smaller at first, gradually climbing as the number of discounted students rises. The full effect of the price change will depend on two additional factors: what happens to the student population, and what happens to costs.

If the population does not change, a 20 percent revenue per student reduction will translate into a 20 percent drop in revenue. If a school has 1,000 students each paying $20,000, its current student revenue is 1,000 x $20,000, or $20 million. If the student price drops by 20 percent, then it will have 1,000 students paying $16,000 each, for total revenue of $16 million.

How big an enrollment increase does the school need to recover that $4 million revenue drop? Reaching $20 million revenue with each student paying $16,000 would take 1,250 students. That’s an increase of 25 percent.

In the real world, though, that 25 percent enrollment increase would not lead to break even. Each of those additional students comes with additional costs for recruiting and teaching. And with an enrollment increase that big, other costs might increase, such as staffing for financial aid.

Let’s assume that variable costs per student are 50 percent of revenue (before the price change). In this example, a student paying $20,000 would incur $10,000 of incremental costs and would provide $10,000 in contribution to profits. At the discounted $16,000 tuition, variable cost per student would remain the same, so only $6,000 would be left in contribution to profits. That’s a 40 percent reduction. Bottom line: in this scenario, it would take a 67 percent increase in enrollment to make up a 20 percent drop in revenue per student.

One conclusion that can be drawn is that the loss of margin is hard to make up with incremental students. However, if prospective students are becoming more price sensitive, this view dooms a school to shrink and possibly die. We would suggest that price reductions must be accompanied by fundamental changes in cost structure, so margins remain largely intact and the volume increases flow to the bottom line. Schools like Grand Canyon, Western Governors, and Brigham Young University in Idaho show that teaching can be done well at much lower cost – under $10,000 per year. In addition, lower prices may improve retention and increase revenue per student.

“Depending on how a price policy change was implemented, it could have the effect of reducing the Title IV share of revenue, improving a school’s compliance.”

Effects of pricing on Title IV eligibility and gainful employment

Profit may not be the only reason to reduce price. Pricing also affects Title IV funding and gainful employment outcomes.

Gainful employment reporting and regulations, while still evolving, are likely to focus on student loan payments and default rates. Lower prices have the potential to reduce student borrowings, which should, in turn, reduce loan payments and default rates. Similarly, to the extent that pricing changes increase completion rates and therefore earnings for students who otherwise would have dropped out, performance on these metrics should improve. However, student Title IV borrowings are not limited to tuition and fees. At least some students are likely to borrow up to the maximum even if tuition dropped. Therefore, any pricing changes should consider how those would interact with Title IV program rules for loan availability.

Changes in pricing could also affect 90/10 compliance. Depending on how a price policy change was implemented, it could have the effect of reducing the Title IV share of revenue, improving a school’s compliance. Again, any potential pricing changes should consider and optimize these effects.

Determining the best pricing strategy

Given the potential effects on revenue, profits, and gainful employment outcomes – and the complexity of the analysis – developing or rethinking a pricing strategy is challenging. We see a half dozen initiatives that education providers can take along this path. In our view, the best approach would combine them all:

Benchmarking:

Researching other schools’ pricing actions can provide insight on the effect of price changes. For example, you can see if lower priced schools are larger or faster growing. For public companies, quarterly reports may indicate whether price changes have led to growth in new student enrollments. This benchmarking also provides basic data on competing offers that you will need to inform your pricing decisions.

“Natural Experiments:”

In the recent past, your school may have changed the length or price of individual programs, creating “experiments” that generated effects on enrollment and retention. Your prices may also vary by program or campus. An analysis of these experiments can provide some insight on the effects of pricing on starts and persistence. Typically, these findings will be limited by the scope of experiments and the many uncontrolled events (e.g., marketing campaigns) that may have taken place during the experiment.

Price-sensitivity research:

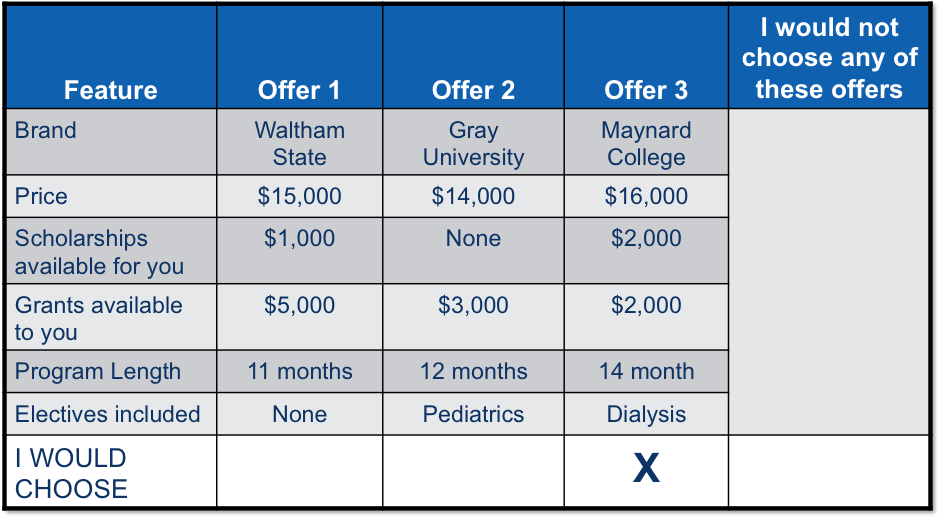

The most thorough way to understand the effects of price changes is to conduct quantitative research with current and potential students at various stages in the student lifecycle. Using conjoint or discrete choice research, you can estimate how price changes would affect starts. You can also test the effect of competitors’ price changes on demand for your school. This work answers the fundamental question: If we lower price, how many additional students will we get?

Redesign cost structure: Getting to fundamentally lower cost takes more than 10 percent across the board cuts. It may require campus consolidations, organization redesign, redefinition of roles, restructuring of overhead, technology changes, and more. Identifying, testing and implementing these changes should precede substantial price changes, or the bottom line may disappear.

Financial scenario modeling: Of course, once you know the price and the effect on starts, you need to understand the effect on your bottom line – and on your student outcomes. Typically this requires a financial model that is tied to the output of the price research. Using this tool, you can run pricing scenarios and immediately see the likely effects of price changes on enrollment and profits. As important, you can also see the effect on average student debt and ability to pay. These price simulation models can also quantify constraints such as financial aid.

Fact-based decision-making: With the benchmarking data and price simulators, management can test alternative pricing strategies, discuss the results, and agree on the approach that makes the most sense for the school and its students.

Of these elements, price sensitivity research may be the least familiar to industry executives. This technique comes out of the consumer goods industry. The starting point is a large survey panel of candidates at the appropriate point in the student lifecycle. Each member of the panel answers a survey that shows them “cards” that illustrate potential offers. (See image.) For each card, they are asked to pick one offer among the ones shown. One alternative is always “I would not choose any of the offers;” this is an important feature of choice research – since “No Choice” is the most common response to new offers in real markets.

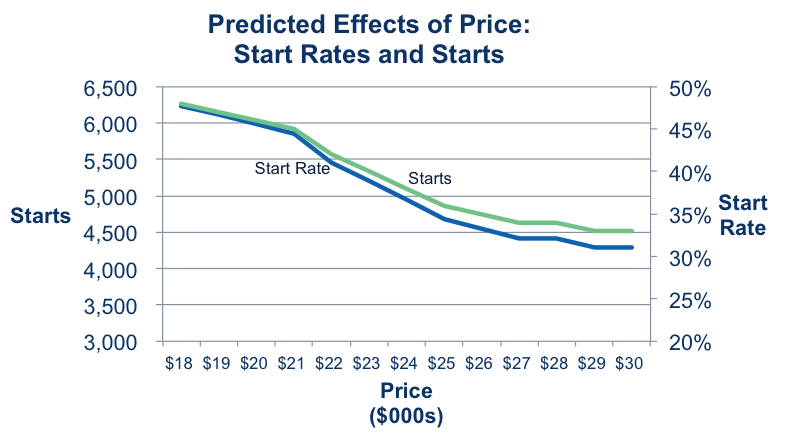

Using the results of this survey and some heavy duty statistics, it is possible to estimate start rates and enrollment rates by feature and level. Here is an example. In this illustration, the start rate declines from 48 percent to 33 percent as price increases from $18,000 to $30,000 for a given program. As a result, starts would decline from 6,240 to 4,290.

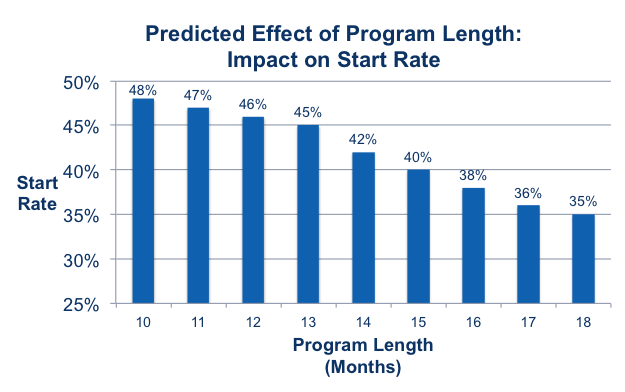

One could also test program length, required electives, and other offer features with this approach. As an example, one could model the effect of program length on starts. In the illustration, the start rate drops 1 percent for each additional month, up to 13 months, and then begins to decline more steeply in months 14 to 17. As with the price chart, the data for this analysis would come from the “choice card” survey, processed with appropriate statistical tools.

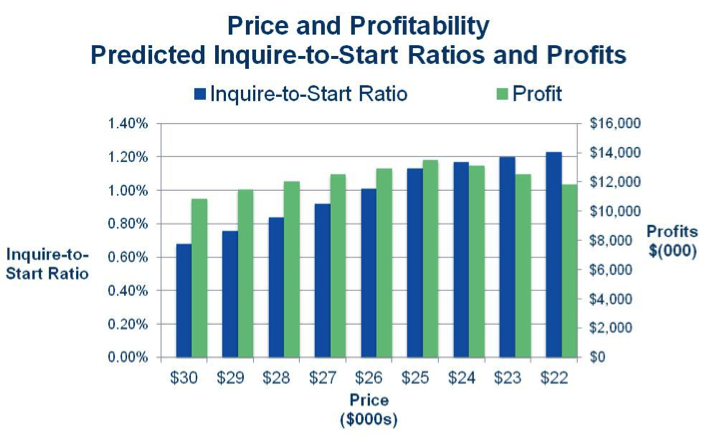

The survey driven data can then feed a financial simulation model, to explore the bottom line impact of price changes. This chart shows the combined effects of changes in the enrollment ratio and the start ratio, combined with the financial model. In this illustration, both the inquire-to-start ratio and profits increase as price drops from $30,000 to $25,000. As price drops below $25,000, profits start to decline.

Conclusions

Pricing used to be easy: Take last year’s numbers, add 4 or 5 percent, and call it done.

Now it’s hard. High profile schools are promoting price cuts and scholarship programs that appear to be worth more than $10,000 per student. Making a change like that is scary and risky. Doing it poorly could be very expensive. But sticking with the old pricing strategy might be every bit as risky.

Fortunately, there are ways for education providers to rethink their pricing strategies that should minimize the risks. In our experience, a combination of price benchmarking, price sensitivity research, financial modeling, cost reduction, and facilitated executive discussion is the best approach.

The difference between a good pricing decision and a bad one – or just standing still – is likely to be in the tens of millions of dollars. How long can you afford to wait?

BOB ATKINS, led Gray’s entry into the education industry and the development of Gray’s proprietary industry databases and service offerings. He has worked with all of Gray’s education clients, consulting CEOs and CMOs on business strategy, pricing, location selection, and program strategy. He is an expert in business strategy, marketing, sales and high-tech distribution channels. He has helped AT&T, Avaya, American Express, Dex Media, Qwest Communications, HP, IBM, Northcentral University, UTI, Alta Colleges and other clients to develop growth strategies, enter new markets, and build their sales and channel organizations. He has also led efforts that have eliminated tens of millions of dollars in cost, particularly in sales and channel management. He is a published author, whose articles have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Sales and Marketing Management, and other publications around the world. He received an MBA, with honors, from Harvard Business School and a BA, magna cum laude, from Harvard College.

Gray Associates, Inc. is a strategy-consulting firm focused on higher education. We help education clients develop fact-based institutional and marketing strategies that maximize outcomes for students, the school, and its constituencies. To support our client work, we have developed an industry-leading database that combines information on inquiry volumes, demographics, competition, and employment. Using this information and proprietary analytical techniques, we work with faculty and school leadership to develop institutional strategies, select programs, pick locations and prepare curricula.

Contact Information: Bob Atkins // CEO and Founder // Gray Associates // 617-401-7662 // bob.atkins@grayassociates.com