Higher Education: How High?

Understanding the Legal Parameters of Possession and use of Medical Cannabis on Campus in States Where it is Legal

By Yolanda R. Gallegos, Lawyer, Gallegos Legal Group

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” – Tenth Amendment

“Respondents … use marijuana that has never been bought or sold, that has never crossed state lines, and that has had no demonstrable effect on the national market for marijuana. If Congress can regulate this under the Commerce Clause, then it can regulate virtually anything–and the Federal Government is no longer one of limited and enumerated powers.” – Justice Clarence Thomas, Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1, 57-58 (2005) (dissent)

“Every time I plant a seed, He say kill it before it grow, He say kill it before they grow.” – Bob Marley

Colleges in states that have legalized medical cannabis use face a unique dilemma: Enforce sanctions against students who are legally authorized in the states to use medical cannabis to alleviate symptoms of illness and disease or risk the loss of federal funding. Just in the last year, three students in health career programs in Arizona, Connecticut, and Florida have sued colleges who chose the former option.1

With the proliferation of marijuana legalization laws in the country, institutions cannot afford to wait until they are sued and must develop sound policies that protect both the medical needs of their students and their federal funding.

The best way to navigate the issue is to be informed about the federal laws that create the dilemma in the first place.

The Controlled Substances Act

The linchpin of the federal-state conflict in cannabis law is the Controlled Substance Act (CSA). Under the CSA, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) classifies drugs under a scheduling system based on their medical value and potential for abuse. The first question the DEA asks in scheduling a drug is whether it can be abused. If the answer is in the negative, the drug is omitted from the schedule. However, if the answer is in the affirmative, the DEA places it on its schedule. Where the drug is placed in the DEA’s scheduling hierarchy depends on its medical value and potential for abuse. Drugs the DEA considers to have low medical value and a high potential for abuse are the most regulated and classified as Schedule I drugs.2 Schedule II to Schedule V drugs are all considered to have some medical value with the higher the schedule number, the lower the potential for abuse.

Since the passage of the CSA in 1970, the DEA has designated cannabis as a Schedule I drug.

Because the research of Schedule I drugs is more regulated, the body of scientific information on the medical value of cannabis is limited. This research restriction has caused a catch-22 for advocates in favor of re-scheduling cannabis because of its purported medical value: Cannabis should not be a Schedule I drug because of its medical value but such medical value cannot be convincingly established because it is a Schedule I drug.

The specific drug that the DEA has placed on Schedule I is “Marihuana.” See 21 U.S.C. § 812(c)(10). “Marihuana” is defined as the Cannabis sativa L. plant with the exception of “hemp”:

(A) [A]ll parts of the plant Cannabis sativa L., whether growing or not; the seeds thereof; the resin extracted from any part of such plant; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such plant, its seeds or resin.

(B) The term “marihuana” does not include–

(i) hemp, as defined in section 1639o of Title 7; or

(ii) the mature stalks of such plant, fiber produced from such stalks, oil or cake made from the seeds of such plant, any other compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such mature stalks (except the resin extracted therefrom), fiber, oil, or cake, or the sterilized seed of such plant which is incapable of germination.

See 21 U.S.C. § 802(16).

Cannabis is a family of plants. Hemp and marijuana are two different species of plants within that family. Although the two plants look similar, the width of their leaves is different. More importantly, hemp and marijuana have different concentrations of THC, the chemical component that causes psychoactive effects or, in the vernacular, causes a high. Hemp is grown for a variety of industrial purposes, such as clothing, rope, and industrial materials.

More recently, hemp is grown to produce cannabidiol (CBD), a naturally occurring compound found in the resinous flower of cannabis. CBD is marketed as a nutritional supplement and pain relief agent. Consequently, although Cannabis sativa L. is a Schedule I drug, the CSA carves out an exception when it grows in the form of hemp. The term “hemp” is defined as cannabis sativa that has no more than 0.3 percent of a THC on a dry weight basis.3 See 7 U.S.C. § 1639o.

Both hemp and marijuana can produce CBD. Both CBD and THC are in cannabis but CBD, unlike THC, does not make a person feel “stoned” or intoxicated. Because of its special status in the law, if CBD comes from hemp plants, it is federally legal, but if it comes from a marijuana plant, it is illegal. But even CBD from hemp is regulated and the Federal Drug Agency (FDA) prohibits the sale of it with any sort of health claims attached to it except for Epidiolex, which is approved for epilepsy. Consequently, a store may sell hemp CBD as long as it doesn’t make any health claims about the CBD-containing product. The FDA, however, has limited enforcement resources so typically, it will only issue a warning letter. States, however, can be more aggressive. For example, local law enforcement in Iowa, Ohio and Texas have raided hemp and CBD in the last year.

Despite this federal exemption for hemp-derived CBD, states sometimes take a different approach. For example, Virginia prohibits the sale of CBD without a prescription.

Ganja-graphy of state laws

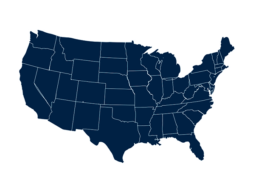

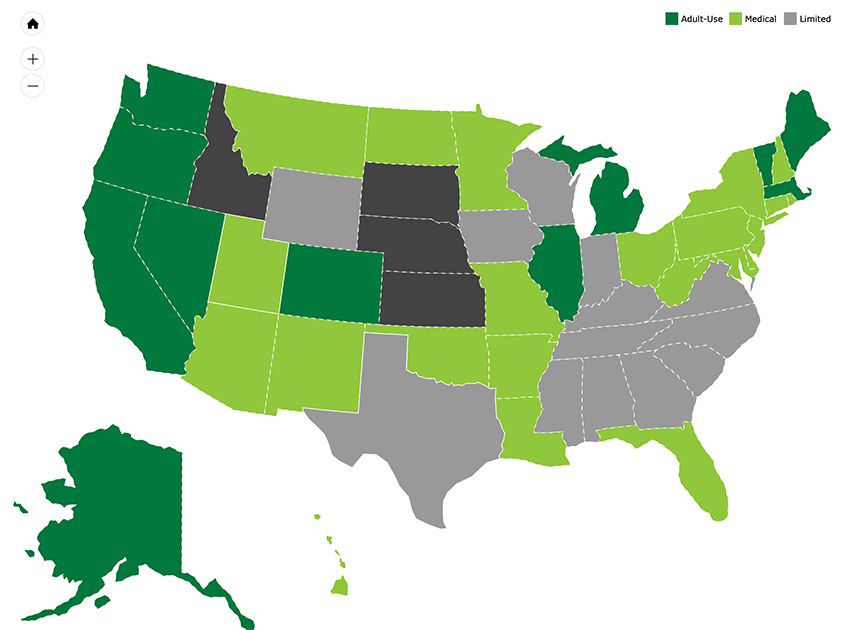

The image below provides a picture of the legal status of cannabis in each of the states.

GANJA-GRAPHY

Summary of legal status of cannabis in each of the states.

Map found at https://thecannabisindustry.org/ncia-news-resources/state-by-state-policies/

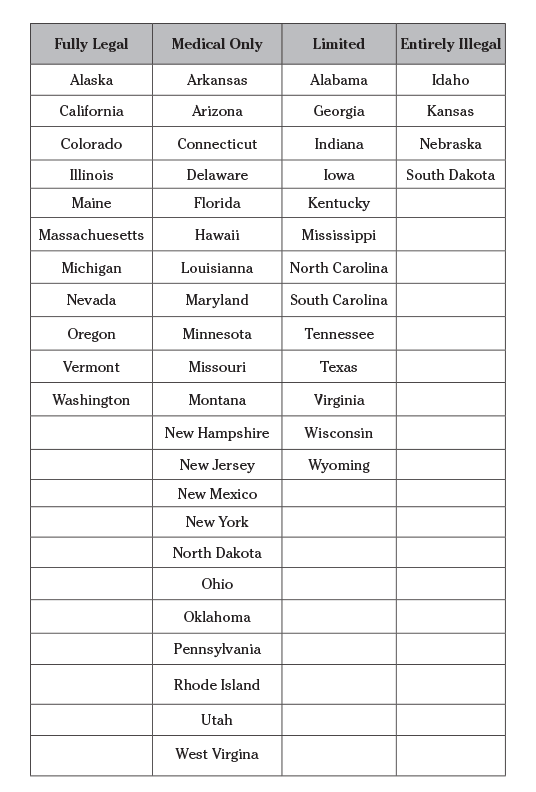

The states in dark gray make marijuana fully legal – both medical and recreational. Light gray is medical use only states. Gray means CBD is permitted. The black states are where marijuana is fully illegal. These states are identified in the chart below:

Thus, there are 11 states where marijuana is fully legal, 22 states where only medical marijuana is legal, 13 states where CBD is legal, and four (4) states where marijuana is completely illegal. Consequently, there are 33 where marijuana enjoys some form of legal status, at least for medical purposes.

The Cole Memorandum’s attempt to resolve the federal-state conflict

Clearly, the marijuana laws of the majority of the states directly conflict with the laws of the federal government. To address this jurisdictional clash, the United States Department of Justice issued a guidance memorandum on August 29, 2013, authored by United States Deputy Attorney General James M. Cole during the presidency of Barack Obama.

The memorandum, known as the Cole Memorandum, was sent to all United States Attorneys and established a policy of limited enforcement of federal offenses related to marijuana.

The memo stated, with certain delineated exceptions, that given its limited resources, the Justice Department would not enforce federal marijuana prohibition in states that “legalized marijuana in some form and … implemented strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems to control the cultivation, distribution, sale, and possession of marijuana.”

The Cole Memorandum was DOJ’s established policy until it was rescinded by Attorney General Jeff Sessions in January 2018. In the Spring of 2019, current Attorney General, William Barr, stated that he was “accepting the Cole Memorandum for now,” but he has also testified before Congress that he has left it up to the U.S. Attorneys in each state to determine what the best approach is in that state, and added that he had “not heard any complaints from the states that have legalized marijuana.” Consequently, the limited safe harbor provided by the Cole Memorandum has been put into question by the current DOJ’s delegation of authority to the U.S. Attorneys state by state.

Triad of federal laws applicable to postsecondary institutions

Clearly, restrictive federal law directly collides with state laws permitting medical and recreational marijuana. If this is the case, why would consumers in droves across the nation risk federal prosecution by purchasing it? Indeed, last year’s cannabis-related revenue in Colorado exceeded a billion dollars and now amounts to 3% of the state’s total annual budget.4 Lax federal enforcement has led many Americans to take this risk.

Should colleges and universities take the same gamble as millions of Americans? Should these institutions simply follow the law of the state in which they are located? For postsecondary institutions, the federal-state conflict carries implications distinct from the average consumer. There are two other federal laws, in addition to the CSA, with which colleges need to comply. These are the Drug-Free Schools & Communities Act (DFSCA), see 20 U.S.C. § 1011i, and the Federal Drug-Free Workplace Act (FDFWA), see 41 U.S.C. § 8102.

A condition for schools that receive Title IV is to comply with the DFSCA and the FDFWA.

The U.S. Department of Education (ED) merged many of the requirements for the FDFWA into the DFSCA, so this article focuses on the DFSCA. The DFSCA was signed into law in 1986 and was part of Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs campaign.

The function of the DFSCA, as originally enacted, was to provide grant funding for drug prevention on campus. In 1989, however, President George Bush signed into law an amendment to the DFSCA which amended the Higher Education Act (HEA) and required schools participating in the programs authorized under Title IV of the HEA to develop a drug prevention program and to make certain disclosures. The core requirements of the DFSCA include the requirements for schools to:

- Develop and implement a program to prevent unlawful possession, use, or distribution of illicit drugs and alcohol by students and employees.

- Disseminate an annual notification to students and employees of:

- Standards of conduct that clearly prohibit the unlawful possession, use, or distribution of illicit drugs and alcohol by students and employees on its property or as part of any of its activities;

- Clear statement that institution will impose sanctions on students and employees (consistent with local, state, and federal law) with a description of sanctions, up to and including expulsion or termination of employment and referral for prosecution, for violations of the standards of conduct.

- Description of sanctions for violating federal, state, and local law and campus policy;

- Description of health risks associated with alcohol and other drug use; and

- Description of treatment options.

- Biennial review of the program’s effectiveness and consistency of the enforcement of sanctions.

See 20 U.S.C. § 1011i & 34 C.F.R. Part 86.

In the context of assessing an institution’s policies regarding marijuana on campus, the most important requirements of the DFSCA are the duties to 1) prohibit the unlawful possession, use, or distribution of illicit drugs; and 2) impose sanctions for violations.

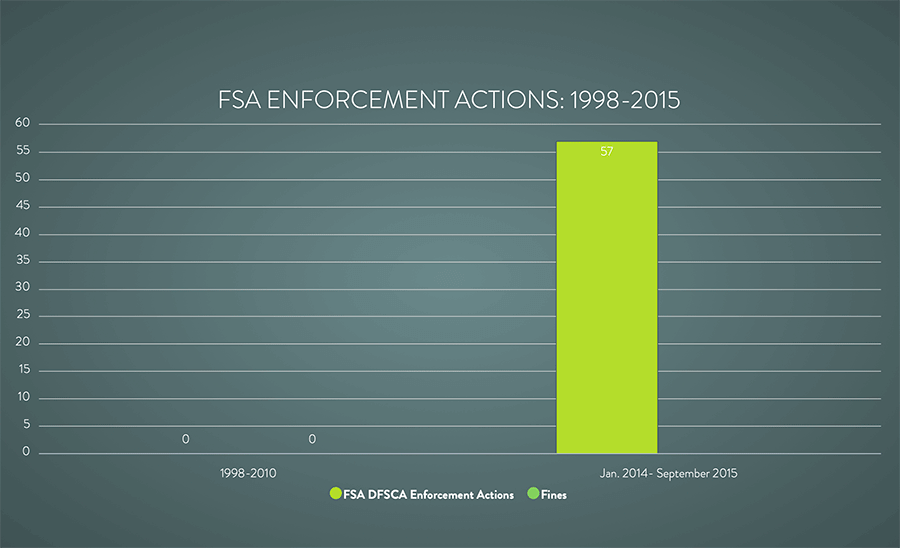

Through the decades, however, schools and even ED had largely ignored the DFSCA. When the law first was enacted it was reported that 700 schools had missed the deadline.5 Decades later in 2015, a survey was conducted showing that only 54% of the responding schools were doing the biennial evaluation. See id. A 2012 Office of Inspector General report regarding the Department’s enforcement of the DFSCA found that the Department had not performed any oversight of postsecondary DFSCA compliance between 1998 and 2010 and provided ineffective oversight between 2010 and 2012.6

But a review of Final Program Review Determinations from ED’s Federal Student Aid (FSA) office shows that ED is increasing enforcement efforts. From Jan. 2014 to September 2015, ED reviewers found 57 institutions in violation of the DFSCA. And the sanctions for these schools ranged from $10,000 to $35,000. I represented a school fairly recently cited with a DFSCA finding and the resources devoted to making the college compliant were time-consuming, expensive, and onerous for the college. The penalty for not complying is losing Title IV eligibility and sanctions of $57,317 per violation. See 34 C.F.R. § 668.84.

(Based on information drawn from FSA’s FPRDs: https://studentaid.gov/data-center/school/program-reviews)

Options

Given the collision of federal prohibitions and state allowances regarding marijuana; should schools participating in Title IV, HEA programs permit marijuana use to the extent permitted by state law? The answer is no. Schools that ignore the requirements of the DFSCA do so at the risk of fines and sanctions up to termination from the Title IV programs. As discussed above, it is clear that colleges must prohibit the possession, use, or distribution of marijuana on campus and they must impose sanctions in a consistent way when a student is found to have violated their prohibition.

Nevertheless, institutions in states that permit medical or recreational use of marijuana may find ways to accommodate such students. Clearly, however, institutions focusing on the medical needs of students stand on firmer ground. For those students, institutions may consider:

- Imposing lenient sanctions such as warnings particularly where the student is using or possessing the marijuana in compliance with state law.

- Having no prohibition for the use of marijuana off campus on non-campus related activities. For example, the University of Colorado has gone so far as to allow students who would otherwise be required to live in dorms to live off campus if they have medical marijuana cards.

Special considerations

If an institution does opt to take a more lenient approach to state-permitted marijuana use, it is well advised to prohibit the following:

- Any form of use or activity that would be illegal under state law;

- Driving under the influence on campus; and

- Being under the influence on campus.

Until Congress takes action to defer to state legislation on marijuana use, campuses across America will continue to have to wrestle with the growing dissonance between federal restrictions and state acceptance of marijuana use. The commonsense approach suggested here does not eliminate risk but tries to find a balance between following the DFCSA and accommodating the medical needs of students in states that permit its use.

Resources:

- “Medical Pot on Campus: Colleges Say No and Face Lawsuit,” Dave Collins, AP (Oct. 24, 2019).

- The CSA describes a Schedule I drug as:

(A) The drug or other substance has a high potential for abuse.

(B) The drug or other substance has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.

(C) There is a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision. 21 U.S.C.A. § 812(b)(1). - The CSA also separately lists as a Schedule I drug, tetrahydrocannabinols or THC, which is the psychoactive component of cannabis, except when it is found in “hemp.” See 21 U.S.C. § 812(c)(17). Thus, the CSA exempts hemp from scheduling in two ways: 1) because of its low THC content and 2) for THC itself when it is found in hemp.

- Borzykowski, Bryan, “Colorado Grows Annual Cannabis Sales to $1 Billion as Other States Struggle to Gain a Market Foothold” (CNBC July 10, 2019).

- Bradley D. Custer, Robert t. Kent, “Understanding the Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act, Then and Now,” 44 J.C. & U.L. 137 (2019).

- Id. (Citing Letter from Wanda A. Scott, Asst. Inspector Gen., U.S. Dept. of Ed. Office of Inspector Gen., to James W. Runcie, Chief Operating Officer, U.S. Dept. of Ed., Federal Student Aid, Institution of Higher Education Compliance with Drug and Alcohol Abuse Prevention Program Requirements, 3-5 (Mar. 14, 2012), available at https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oig/aireports/i13l0002.pdf.

YOLANDA GALLEGOS established her law firm, Gallegos Legal Group, in 1998 and has represented private sector schools throughout the country for 30 years. Her practice focuses on guiding postsecondary schools through critical events such as governmental and accreditor investigations, corporate expansion and downsizing, and operational adjustments required in response to regulatory changes.

Yolanda has served as an expert witness in federal and state courts on matters related to the regulation of student financial aid and is a frequent speaker and writer on a variety of regulatory topics affecting higher education including her chapter on the Violence Against Woman Act regulations, which was published by Thomson Reuters in its book, “Emerging Issues in College and University Security.”

Yolanda has successfully defended dozens of institutions in program reviews and audits before the U.S. Department of Education and she has extensive experience in accreditation, and state licensing.

Yolanda received her J.D. from the University Of New Mexico School of Law and her LLM in Advocacy from Georgetown University Law Center. She is a member of both the District of Columbia and New Mexico Bars. She is a recipient of the D.C. Bar’s Pro Bono Lawyer of the Year award for her representation in litigation for a Central American immigrant.

Contact Information: Yolanda R. Gallegos // Lawyer // Gallegos Legal Group // 505-242-8900 // yolanda@gallegoslegalgroup.com // http://www.gallegoslegalgroup.com/