What Industry Says is Missing in Their Entry-Level Graduates – And What They’re Willing to do to Fill the Gap

By Wallace K. Pond, Ph.D., www.WallaceKPond.com

Introduction

For several years there has been a discussion within industry, government, and post-secondary education about the growing “skills gap,” primarily within vocational and technical fields. That discussion has become more urgent as millions of jobs go unfilled across industries as varied as healthcare and transportation. A related, and equally important discussion dealing with “in-demand skills” has also experienced increased urgency. This refers to applicants who have basic qualifications, training, or even licensure for a position, but do not have specific knowledge or skills required by the employer to be fully effective on the job. An example might be a Health Information Technologist who has basic billing and coding skills, but does not have database administration skills or a diesel mechanic with overhaul skills that cannot perform digital diagnostics. This applies broadly to knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) and may also include gaps in “soft,” non-technical areas.

“We are at a place in which ‘tradespeople’ can no longer just be folks who couldn’t or wouldn’t go to university. The complexity of the work we are doing requires technicians who are competent STEM thinkers.” -HVACR industry representative

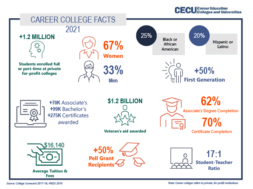

To better understand this situation, in the spring of 2019, Career Education Colleges and Universities (CECU) contracted me to conduct a research study to assess what gaps might exist between graduate KSAs versus what industry needs those graduates to know and be able to do in the workplace. The project included multiple, extensive real-time interviews with representatives in each of the eight industries reviewed, as well as reviews of industry reports and surveys, training programs, and industry-related literature. The industry-specific data, which is not discussed in this article, reflect baseline In-Demand KSAs, New KSAs, Future KSAs, and Missing KSAs (defined later in the article). The industries were chosen based on the volume of graduates that career colleges produce in those career fields. You can see the full report here (https://www.career.org/skilldemands.html)1.

While some of the findings will seem familiar and could have come from a similar study years ago – particularly as the skill demands relate to “soft” skills – some of the findings reflect clear changes in industry needs and, surprisingly, the lengths that some employers are willing to go to close the gaps in technical, soft, and business support skills.

High level findings

The full report provides detailed findings, both across industry, and within specific industries, but for the purposes of this article, career colleges and universities would be well served by contemplating the following conclusions.

- The pace of external change, within industry and the “real world,” is vastly greater than the pace of change within higher education (including career colleges). This is a structural challenge resulting in increasing gaps between program curriculum and industry needs.

- The number one solution to the “pace of change” problem is to change industry relationships from “peripheral” to “embedded.” (Fortunately, industry is ready and willing to deepen partnerships with career colleges to better meet evolving in-demand skills).

- Virtually all jobs in all industries now require that employees work with computer applications and technology driven automation at some level.

- Current accreditation requirements sometimes inhibit innovation and delay necessary program revisions and updates.

- Virtually all vocational-technical fields require entry level (after graduation) and continuous, on-going training for employees. That training is not currently being provided by career colleges, but rather by industry. This is a significant, potential opportunity for sector schools.

- There are potentially significant changes on the horizon such as hybrid job positions, wholesale industry disruptions (autonomous vehicles, machine learning, cyclical/perpetual education and training) that could have major implications for industry and career colleges.

- While the current pace of change and resulting KSA gaps present risks to the career college value proposition, there is no other sector of higher education that is as industry focused and whose programs are more job focused. There is a solid foundation on which to address identified challenges and opportunities for schools that are up to the challenge.

- The expansive growth of industry-delivered training, even ab-initio training, presents a bona fide threat to the career college diploma/degree program model and is already happening at scale in some industries.

The research also identified high-level recommendations that career colleges can follow to address the identified challenges. More detailed recommendations are at the end of this article.

- Redesigning and deepening industry partnerships

- Shortening curriculum review and revision periods

- Aligning program learning outcomes with industry provided KSAs

- Designing programs for the future rather than the present, with curriculum “placeholders” that can be quickly revised

- Embedding faculty in industry and industry in the school

- Redesigning internships/externships to be closer to actual work experience

It is important to understand that the research referenced in this article, simply reflects what industry and professional organizations communicate as in-demand and future KSAs for entry-level workers. Those KSAs may or may not be the responsibility of educational institutions. Moreover, the industry feedback applies to a broad cross section of entry-level employees. There is undoubtedly a great deal of diversity from one career school graduate to another and between schools in terms of curriculum, instruction, faculty, industry partnership, and learner outcomes.

“Education is willing to be a partner, but there is a gap between curriculum and industry needs and between instructors’ currency and industry reality.” -PAC Member

The project was limited to the following industries, which represent the highest percentage contributions to the workforce from career colleges:

• Healthcare

• HVAC(R)

• Cosmetology

• Transportation/Logistics/Materials Moving

• Information Technology

• Manufacturing

• Culinary Arts

• Automotive/Diesel Mechanics

The industries represented in the study generally include multiple individual jobs within an industry category, but overall reflect disciplines in which career colleges graduate between approximately 30 percent and 90 percent of the practitioners in the field. The scope of the project did not allow for in-depth analysis of each discreet job within an industry. As such, each category reflects industry perspectives that apply generally across the career field.

Due to space constraints, industry specific information is not provided in this article, but can be easily accessed in the full report. That data is provided across four domains: In-Demand KSAs, “New” KSAs, Future KSAs, and Missing KSAs, defined in the table below.

| In-Demand KSAs | New KSAs | Future KSAs | Missing KSAs |

| Baseline knowledge and skill requirements, which may be a combination of long-standing and evolving KSAs | Relatively recent, but not necessarily cutting edge knowledge and skill requirements | Skills, knowledge and abilities that are very likely to be required in the future based upon impending changes in industry | Required knowledge and skills, either baseline or relatively new, that industry reports graduates should have, but are often missing |

Common demands across industries

Not surprisingly, despite vast differences in the nature of disparate career fields, the research identified common gaps between industry needs and graduate entry-level knowledge, skills, and abilities, with a common concern that the equipment used in schools is often outdated relative to what employees will use in the field. Some gaps are technical in nature, particularly relating to digital and computer technologies, while others are “low tech,” but equally important soft skills and personal traits.

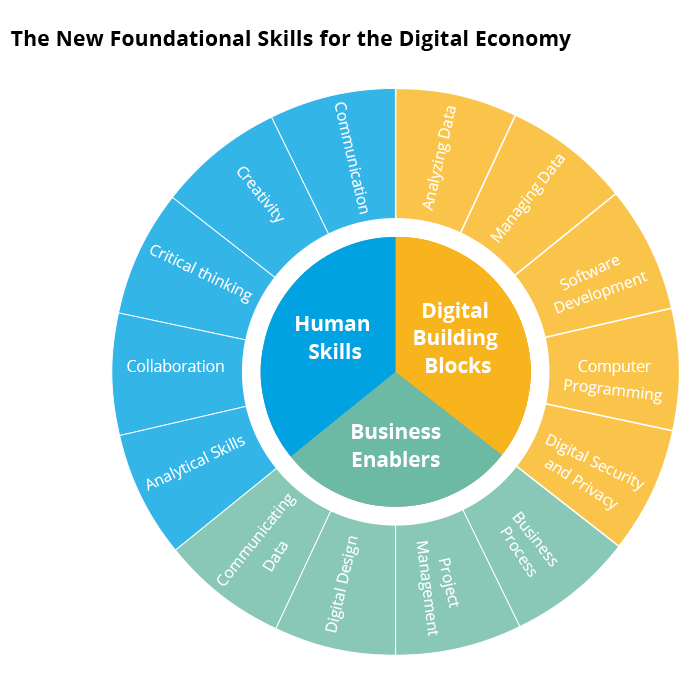

A clear trend is that the digital economy is requiring what Burning Glass2 and the Business-Higher Education Forum3 have identified as 14 “New Foundational Skills,” which transcend all industries and jobs in three main domains: Human Skills, Digital Skills, and Business Enabler Skills. All 14 skills do not apply in all workplace contexts, but the framework of soft/relationship skills, digital-technical skills, and application of those skills to enable business outcomes, have implications for all curriculum development efforts across all career-focused programs, both because they are documented employer needs, but also because they translate into greater employability and higher compensation for the graduates that possess those skills.

These 14 skills, already in wide demand by employers, command salary premiums and are crucial for workers who want to keep pace with a changeing job market.

The research for this project also found that many in-demand skills are not necessarily “new.” In other words, many skills that were in demand, even years ago, are still often inadequate or missing in entry-level graduates entering a wide variety of fields today. In fact, the items in the table below have at least some application in each of the eight industries studied.

| Technical In-Demand Skills | Soft Skills and Personal Traits |

| Automation-Tech/Human Interfaces | Writing/Communications |

| Use of ERP Computer Applications | Customer Relations/Sales |

| Data Management | Dependability/Accountability |

| Programming | Prioritization and Critical Thinking |

| Computation | Social/Emotional Intelligence |

| Environmental Compliance | Problem-Solving |

| Design/Installation | Show Up and Be Drug Free4 |

Entry level and ongoing industry training

Due to the extremely rapid pace of change in vocational-technical and health science fields, the research suggests that regardless of the training that graduates initially receive in school-based programs, their long term employability in their chosen field will require continuous re-training over time. Based on employer and professional organization feedback and reports, the on-going training is currently taking place primarily within industry, but there is no reason that such updated training could not be offered by career colleges in partnership with employers and professional organizations.

“We simply find that not only the quantity but the quality of what’s being produced out there by the educational system doesn’t necessarily meet our needs.” -Transportation/Logistics industry representative.

In fact, in order to be viable, the future school model might have to include regular post-graduate training opportunities with curriculum that comes directly from industry. Such training might be either a benefit offered to alumni or a revenue opportunity, depending on how it is structured. Regardless, it is essential that career colleges think of technical training as an ongoing endeavor and determine what their role will be in delivering that training in a post-graduation context.

Of potentially greater concern are the massive investments that many industries are already making in entry-level training for their employees. In effect, some employers have determined that it is cheaper to invest even tens of millions of dollars in ab-initio training, which they control and whose graduates become their employees, rather than depending on college trained graduates, to whom they will have to offer new employee training anyway! This is already happening at scale in the automotive, transportation, IT, hospitality, aviation, healthcare, and plumbing/welding industries and is growing in culinary as well.

Summary and key recommendations

1. The pace of change across all industries is so great, particularly related to evolving technology, that it is unrealistic to think that school-based programs can provide fully up to date curriculum, equipment, and instruction at all times. As such, the industry view is that at the very least, programs must provide graduates very solid fundamental skills regardless of the field, with the reality that virtually all graduates will require some level of initial training in the workplace as well as continuing training over time. Some industries such as HVAC, Automotive Mechanics, IT and Healthcare, budget substantial sums for training of entry-level employees. Examples of fundamental skills include terminology, tool/equipment recognition and use, basic systems and computer applications, basic theoretical foundations, computational skills, and safety, along with a host of soft skills such as punctuality, written and spoken communications, critical thinking, ability to work with others, customer relations, and follow directions, and an openness to lifelong learning.

“We know that schools cannot teach everything and that their equipment and instructors will not always be up to date, but graduates need to know the difference between calipers and pliers and they need to have basic hands on skills with the equipment they will use on the job.” -HVACR industry representative

2. Career colleges would benefit from deeper, more productive outreach to industry. Of the more than a dozen conversations I had, only one person reported having been asked about “in-demand skills” from the education side. The traditional PAC model of one (if that) meeting per year is not adequate. Educational institutions need to have “embedded” relationships with industry in which stakeholders from both education and industry are regularly, directly involved in the other’s world. Curriculum itself must be viewed as a dynamic and flexible process rather than a static product and it should be driven by industry as much as by faculty or academic SMEs.

3. Industry is asking for things that schools often cannot do under current accreditation rules. Therefore, to meet industry requirements, accreditors need to:

- Provide schools the flexibility to update curriculum on the fly in partnership with industry without regard to arbitrary percentages of content.

- Support new program approvals in a fraction of the currently required time.

- Allow schools to hire the best instructors rather than instructors with the “right” academic credentials.

- Allow flexibility with the Carnegie model for determining credit and shift to a competency-based model so that schools can deliver programs that will achieve desired graduate outcomes rather than artificial contact hours and seat time.

Three key strategies for improving the readiness of graduates in all fields

Although the challenges are real, feedback from industry representatives reveals three high level or “structural” strategies that schools can use to narrow the KSA gaps.

1) Deeper Industry Involvement and Partnership (with ground level, continuous input in new programs and for program revisions)

- Should happen at least annually in each program

- Curriculum should be based, in part, on in-house industry training

- Industry placement of faculty and institutional roles for industry

2) More Extensive and Realistic Internship/Field Experiences

- Internships should better reflect the real world the graduate will work in

- School labs need to better reflect workplace environments

- More hands-on training using industry equipment in industry settings

3) Curriculum Based on Fundamental Principles

- New functional skills

- Industry based principles that are foundational for future training (scenario based education, i.e., here is a real-world problem, how would you solve it?)

- STEM/Computation/Critical thinking

Related issues

The research in the report determined that there are numerous issues related to changing industry and market realities and requirements that have implications for career colleges as they revise existing programs and plan for new ones. Those include:

- New functional skills

- Hybrid jobs

- Disruptions to existing industries and jobs

- Cyclical or ongoing nature of training

- Differences in geography or other contexts

New functional skills

Regardless of the industry, changes across society and the workplace have fundamentally changed what is required for the success of employees and the organizations they work for. As such, all career programs in all disciplines must ensure that graduates:

- Are facile in the technologies relevant to their fields

- Can work with others in highly diverse environments

- Are enablers of the business in which they work

Hybrid jobs

Most vocational-technical programs are currently designed as stand-alone programs to train students for specific jobs, e.g., LPN, welder, computer programmer, etc. However, the research conducted for this project suggests that going forward more and more jobs will actually combine the skills and outcomes of what are now multiple, discrete positions. In fact, based on current industry trends in areas such as transportation, healthcare, manufacturing, and IT among others, employees are already filling “hybrid” positions, for which they were trained on the job or through other industry credentials. Going forward, career college programs may not lead to gainful employment if the structure of those programs does not change. Examples might be application developers that are also data managers, truck drivers that are also logistics technicians, or Licensed Practical Nurses that also manage patient data.

Disruptions to existing industries and jobs

The research discussed here is based on industries as they exist and are understood today. There are inevitable disruptions in play now and on the horizon that will dramatically change how people work and thus how they are educated before entering any given industry. One of the most currently talked about industry disruptions on the horizon is related to autonomous vehicles. Another is machine learning automation of even “middle” level tasks. A structural challenge with academic programs today is that the development, approval, and implementation cycle is markedly slower than the pace of change in industry. As a result, programs today generally experience elements of obsolescence before the programs are even launched. Career colleges must fundamentally alter the current program development process so that it is driven by industry needs, is based on a generalist as well as a specialist focus, and happens in a fraction of the time it currently takes to launch new programs or revise existing programs. See the note above about the role of accreditors.

Cyclical education and training

Surprisingly, even in 2019, virtually all career college programs are designed with a beginning and end, at which point students graduate and go into the workforce. This is completely counter to the real world construct of immediate entry-level training by the employer to address in-demand KSAs, followed by continuous, on-going training to ensure sustained employee viability. In the current career college structure, the life-long training and education needs of graduates are fully surrendered to industry, further compromising the value proposition of the student-graduate and employer relationship with educational institutions. In other words, the current school model is based on a “one and done” approach, whereas the real world is based on a cyclical model of never-ending education and training. The future viability of career colleges may be more at risk from this reality than any other reason.

Urban versus rural and other context differences

The research behind this report revealed that there are significant differences in training at the school level and practice in industry based on different contexts such as urban versus rural and north versus south. The size and comprehensiveness of the educational institution is also a factor. For example, a small HVAC program in South Texas is likely to focus more on air conditioning than on radiant heat and graduates are likely to face skill deficits for employability in northern climates. Similarly, LPNs and RNs who practice in small, rural hospitals are likely to have an expanded scope of practice and be seen more as generalists than clinicians with the same credentials who practice in large, urban or suburban hospitals. Private practice nurses are more likely to have back office and customer facing responsibilities than those in acute care facilities. Representatives across different industries noted that educational institutions shouldn’t train students solely for the environment in which the school is located. The curriculum should include the full spectrum of realities across the country that a highly mobile workforce will encounter. As an example, a representative of the trucking industry noted that they often get entry-level drivers who have never driven a truck in the mountains, in high winds, or in snow, and learn for the first time in real conditions, hauling a load on the open road, which is not necessarily the safest way to get such experience. There are similar examples in healthcare, IT, etc.

In short, to ensure viability going forward, in addition to the topics related to industry relationships and dynamic curriculum, career colleges must be cognizant of concepts such as hybrid jobs, industry disruptions, and “cyclical” training among other identified areas. If not, the current industry trend toward in-house training could render many current vocational-technical programs obsolete.

Greatest opportunity

The greatest risk for career colleges is also the greatest opportunity: the shift in ab-initio training to industry as well as ongoing training after graduation. Although this is happening in essentially every career field, the greatest scale opportunities are in Healthcare, IT, and Automotive/Diesel Mechanics, where industry is spending hundreds of millions of dollars annually on training for employees who have already been to school! As noted previously in this report, almost none of that training is being provided by career colleges. It is either being delivered in-house or is contracted out to “corporate” training companies and professional organizations.

This opportunity is three-fold:

- One, it is another avenue for building school-industry relationships, partnerships, and credibility.

- Two, it is a financial opportunity that is similar in scale to the current credit-based program models for ab-initio education in career colleges.

- Three, it is a means to establish life-long relationships with graduates who are “repeat customers,” often sponsored by third party payers.

It is essential, therefore, that, at a minimum, career colleges do two things:

- Ensure that credit-bearing programs broadly meet the needs of employers at the point of student graduation. Comparing existing program learning outcomes with the industry feedback in the full report would be a good place to start.

- Engage industry as an ongoing training partner for the cyclical, post-graduate training that is now required in effectively every career field represented by career colleges today.

Conclusion

While the research contracted by CECU provides much food for thought, and some genuine cause for concern, it also suggests that there are tangible strategies for addressing most of the in-demand KSA gaps. It also suggests that industry is generally very open to deeper relationships. Moreover, while the research referenced in this article was based on career college graduates, the challenges noted are often far greater in “traditional” institutions of higher education, which generally have less robust relationships with industry, less applied curricula, and are even more constrained relative to timely changes and innovation. As such, while the challenges and risks are real, career colleges are structurally better prepared to address the issues should they choose to do so. Any institutions that would like assistance in assessing their current practice and likely solutions to addressing both the KSA gaps and the related value proposition for students and employers can contact me directly through www.WallaceKPond.com.

Resources

- https://www.career.org/skilldemands.html

- https://www.burning-glass.com/research-project/new-foundational-skills/

- http://www.bhef.com

- This comment was made more than any other during my interviews.

DR. POND has been a mission-driven educator for over 30 years. For the last 20 years, Wallace has been a senior leader in higher education, holding both campus and system level positions overseeing small and large, single and multi-campus and online institutions of higher education in the US and internationally. He has served as chancellor, president, COO, CEO, and CAO (Chief Academic Officer), bringing exceptional value as a strategic-servant leader through extensive experience and acumen in strategic planning, change management, organizational design and development, P&L, human capital development, innovation, new programs, and deep operational expertise among other areas of impact.

Dr. Pond began his career as a high school teacher and adjunct professor, and spent six years in the elementary and secondary classroom working primarily with at-risk youth. Wallace was also a public school administrator and spent another six years as a full-time professor and administrator in the not-for-profit higher education sector, working in both on campus and online education, bringing education to underserved students. Additionally, Wallace has over 15 years of executive, private sector experience, creating a unique and powerful combination of mission-driven and business focused leadership.

Dr. Pond has lived, worked, and studied in North America, Latin America, the Caribbean, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. He has presented nationally and internationally and is the author of numerous articles and the book, The Lights Are On, Is Anybody Home? Education in America.

Wallace, a licensed pilot, has a BA in Spanish, an M.Ed in Human Resource Education, and a Ph.D. in Education. He resides with his wife and youngest daughter in Colorado and, until recently, the United Arab Emirates.

Using all of his diverse and comprehensive domestic and international experience, Dr. Pond consults across a broad range of leadership and educational areas via www.WallaceKPond.com.

Contact Information: Wallace K. Pond, Ph.D. // 719-247-0486 // wkp@wallacekpond.com // www.wallacekpond.com