Data Shows Career Colleges Fare Well When Compared to Public and Nonprofit Sectors

Written by Sara Klein from a CECU Hill Day presentation by Nicholas Kent, Senior Vice President of Policy and Regulatory Affairs, CECU

Career colleges compare quite favorably statistically to other institutions, which was explained in a detailed presentation of the CECU 2021 Factbook. On March 23, 2021, at Hill Day, Nicholas Kent, the Senior Vice President of Policy and Regulatory Affairs at CECU, explained how well career colleges preform and how this data-rich information can help schools have conversations with policymakers.

Kent began the presentation by explaining how the Factbook could be an aid in discussions with policymakers at the national and local level by giving basic facts about career colleges and helping address any misconceptions or misunderstandings.

“What the Factbook does not do, however, is tell the story of your institution and the students you serve,” Kent said. “That is only a story that you can tell, and you should be telling that story.”

Kent continued by offering some advice, such as explaining that the Factbook can help schools be prepared to answer questions about how well they serve the students in their school’s communities. He explained how it’s important to be familiar with the college scorecard, as members of Congress and their staff will often review this data before meeting with a school. The last piece of advice he gave was to not overwhelm the policymaker with all the facts and statistics in the Factbook, but to instead pick out data points that help support your school’s story and to use them to inform the conversation.

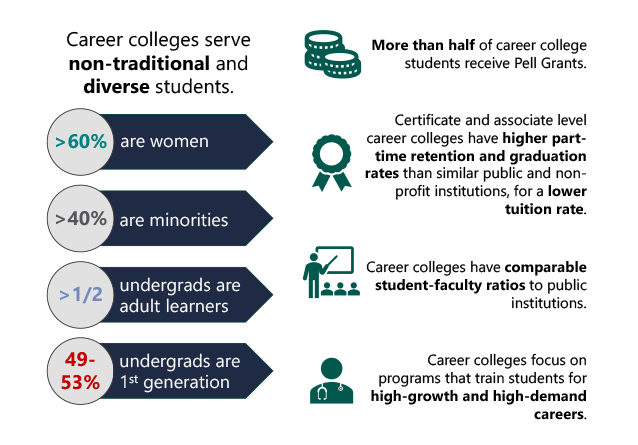

Kent then went on to discuss the quick points of the presentation, focusing on the fact that career colleges serve non-traditional and diverse students, which the data supports.

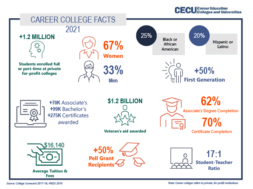

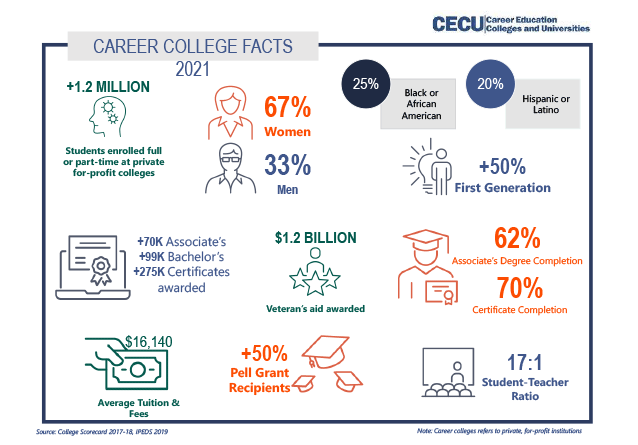

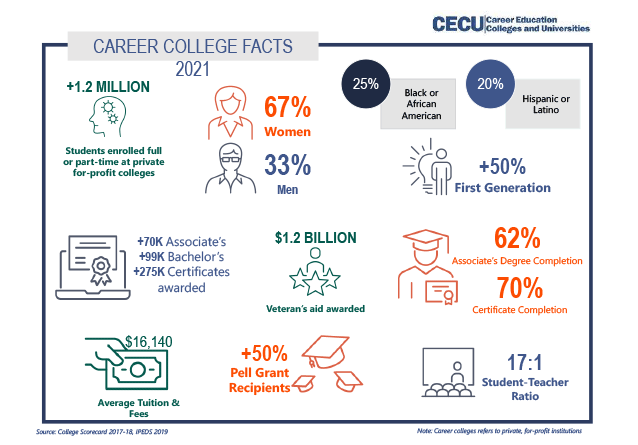

“Over 60% of the students that we enroll are women, over 40% are minorities, and 50% are first-generation students,” Kent explained, pointing to the 67% women and 25% Black or African American and 20% Hispanic or Latino statistics. Additionally, half of career college students receive Pell grants. Certificate and associate level career colleges have higher part-time retention and graduation rates than similar public and non-profit colleges, with lower tuition rates. He pointed out that the students and faculty ratios were similar to public institutions and that career colleges focus on programs for high growth and high demand careers.

“Over a full academic year, private for-profit colleges enroll about 1.2 million part-time or full-time students in the United States,” Kent said, with a high concentration of students in California and Arizona. This number is based on fall enrollment numbers. Looking at a 12-month enrollment figure, the number increases to closer to 2 million students.

Kent went on to discuss the context behind how the for-profit school sector is growing while others are contracting. He explained how the total enrollment of for-profit institutions has been in a steady decline of around 50% since a decade ago, with 1.9 million student enrollments today compared to 3.9 million in 2010, so the sector is significantly smaller than it was. While the sector has grown 5.3%, or 40,000 students, over fall 2019, it is a very small representative sample out of the 17.5 million students that comprise all sectors.

Student diversity was another topic Kent expanded on, discussing how 25.3% of students are Hispanic at for-profit less than two year, while the public sector is only at 16.6%, and 25.6% of enrollments are African American students compared to 10.1% at public schools.

Student diversity was another topic Kent expanded on, discussing how 25.3% of students are Hispanic at for-profit less than two year, while the public sector is only at 16.6%, and 25.6% of enrollments are African American students compared to 10.1% at public schools.

Diversity also comprises the employees at for-profit schools, with four-year and two-year institutions employing about 115,000 employees (as of Fall of 2018), with “over a third (37%) being black, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander Alaskan, or two or more races,” Kent said.

Career colleges also serve more nontraditional students than the other sectors. For-profit four-year colleges enroll 65.2% of their student population over the age of 25, while nonprofit schools enroll 24.5% and public schools enroll 22.9%. Besides age, nearly 50% of for-profit institution students are first-generation.

“Clearly, we serve a very diverse student body in terms of gender, ethnicity, age, and first-generation status,” Kent explained. “These are the students we serve, and we should be proud of serving those students.”

In addition to a diverse student body, for-profit organizations serve many military and veteran students. Some critics state that for-profit schools serve a disproportionate number of these students. This isn’t true, according to the data. “Approximately 1 to 2% of undergraduates at career colleges are veterans and that is pretty proportional to the other sectors,” Kent said.

In fact, the number of military and veterans is actually higher at public less than two-year institutions, at 4.6%, versus for-profit less than two-year schools, which have 2.3% military and veteran students.

Access is another area that for-profit schools do well in. “Career colleges typically admit a larger share of applicants than institutions in other sectors and have a higher admissions yield,” Kent explained. Admissions yield is the desire of the student to attend an institution. The higher the percentage, the more likely it was at the top of the applicant’s choices for colleges. The lower the percentage, the more competitive it is for an applicant to be admitted.

“We have generally both higher admission yields, as well as higher rates suggesting that we are much more open access than other sectors,” Kent explained. Public less than two-year schools have a slightly higher admissions yield, at 77.6% versus 76.6% at for-profit schools, which is the only exception, and still very similar. “This suggests to policymakers that we do have an open access policy, that we are taking non-traditional diverse students and welcoming them with open arms and giving them the opportunity that other sectors are not providing to them in terms of the ability to move up the social and economic ladder.”

Career colleges enroll more undergraduates receiving Pell Grants than the public sector, and more two-year career college students receive financial aid than at community colleges. “This suggests that the students that we serve are from low-income backgrounds,” Kent said.

Student outcomes are an important aspect, along with retention and transfer rates. Career colleges retain more part-time students than nonprofit and public schools and have a higher retention rate for certificates and associates, and a lower transfer outright. “This shows us that our students want to stay with us. They want to graduate from us, and they’re not interested in moving to another institution,” Kent said.

The retention rates are better at career colleges than public institutions. The percent of first-time, full-time undergraduate students was 66% at for-profit colleges compared to 61.9% at public two-year institutions. For part-time students, 51.3% stayed at for-profit colleges compared to 44.7% at public schools and 38.5% at nonprofits. At the associate level, it’s 63.2% completion at for-profit versus 33% completion in the public sector. For Pell recipients getting an associate degree, 65% complete their degrees at for-profit schools versus 31% at public schools. In addition, the graduation rates at for-profit schools are more than doubled than those at public two-year colleges.

“For the 2015 starting cohort, for example, graduation rates from the first institutions attended within 150% of normal completion time for first-time, full-time students seeking degrees and certificates was 61.5% at for-profit institutions compared to 27% at public two-year institutions and 62.3% at private nonprofit institutions,” Kent said.

Four-year career colleges report lower average tuition and fees than private non-profit institutions, with $16,139.56 versus $27,492.59. In addition, bachelor degree graduates from career colleges have on average a higher median first-year earnings at $41,638.34 versus $39,882.36 at public schools and $40,159.53 at non-profit schools. “When it comes to what students are earning after they leave our institutions, many students fare very well at proprietary institutions. It is a good investment for them,” Kent said. The Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce has a report that looks at public, private, and for-profit schools to rank the return on investment of those institutions. “If you did very well, you should boast about that. You should talk about that with policymakers”

Two-year career colleges report lower median debt than non-profits, but higher debt at four-year institutions. By award, career colleges result in lower debt for certificates. The higher debt at for-profit colleges for a bachelor’s degree can be explained to policymakers, though. “For example, in 2017 18 public degree-granting institutions receive about 30%, which represents about $122 billion, of their total revenues from state and local governments compared to less than 1% directed at private institutions and 0.2% for private for-profit institutions,” Kent explained. “So when we talk about why debt is sometimes higher at for-profit institutions, it may be because we are not getting $130 billion worth of state and local subsidies annually.”

The student-to-teacher ratio for career colleges fare better or are very comparable to other sectors. At the four-year for-profit level, it’s 17 to one, which is comparable to public four-year institutions. At two-year institutions, public schools are 18 to one with for-profits being 17 to one. “Here is one data point that suggests that we are very much in line with other sectors of higher education,” Kent said.

Career colleges award more degrees in fields with expected occupation gaps and higher projected growth, such as healthcare occupations.

“When it comes to healthcare, social services and computer occupations requiring at least an associate degree projected to grow in the next 10 years, for-profit institutions have the programs in those needed areas,” Kent said.

For-profit colleges are in alignment with projected workforce needs and demand. Areas like culinary, entertainment, and personal services have the vast majority of workers from the for-profit sector. “44.3%, on average annually, of our graduates are going to these jobs. 31% of our graduates are going into health-related professions,” Kent said. “Many of our graduates were on the front lines of COVID-19 and really helped to support their communities.”

Kent concluded with how necessary to the workforce career colleges are. “When it comes to associate degrees, 41.2% of all associate degrees that we awarded as a sector were in the health professions and related programs,” he said. “[In addition,] we are putting out more mechanics and welders and HVAC technicians than the nonprofit schools.”

For more information on the CECU’s 2021 Factbook visit https://www.career.org/.

NICHOLAS KENT is Senior Vice President of Policy and Regulatory Affairs at Career Education Colleges and Universities. In this role, he serves as senior advisor to association leadership by providing statutory, regulatory, and policy guidance on matters relating to higher education.

Prior to his current role, Nicholas was Managing Director at Dulles Advisory Group, a higher education and strategic management consulting firm. In this position, he worked with postsecondary institutions to assist and guide them on the vastly regulated field of higher education, including advising nonprofit and proprietary organizations regarding strategic and technical issues pertaining to accreditation and the federal student financial assistance programs.

Nicholas previously held a government appointment as Director of Policy, Planning and Research at the District of Columbia Office of the State Superintendent of Education. In this position, he was primarily responsible for working with internal and external stakeholders to develop and support the final issuance of regulations, policies, and guidance materials that supported the agency’s efforts to ensure compliance with federal and local laws.

Before time in public service, Nicholas served as Vice President of Legislative and Regulatory Affairs for a private equity sponsored company. For approximately eight years, he was responsible for leading and managing regulatory operations, including accreditation and state authorization activities, for a system of 53 postsecondary institutions.

Nicholas began his career in education as a professional staff member for an accreditation agency recognized by the U.S. Secretary of Education.

Nicholas earned his bachelor’s degree in political science from West Virginia Wesleyan College and his master’s degree in higher education administration with a concentration in policy from The George Washington University. He is a current member of the Association for Education Finance and Policy and a frequent writer and speaker on topics related to higher education.

Contact Information: Nicholas Kent // Senior Vice President of Policy and Regulatory Affairs // CECU // nicholas.kent@career.org // 571-800-6524 // https://www.career.org/