How Career Colleges Can Thrive in Uncertain Times

By Rob Herndon, President, Entrepreneurial Learning Initiative

In uncertain times there is no better group of people to emulate than everyday entrepreneurs. Individuals who have overcome difficult circumstances in their lives with integrity, persistence and optimism while creating great value for others through their work provide a tremendous roadmap for the rest of us to follow when the world seems out of control. The military coined the term “VUCA” at the end of the Cold War to describe the future state of the world as more volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous, and the way things are going, they seem pretty prescient in 2020.

Luckily our organization has been studying these underappreciated individuals for the last 13 years.

Everyday entrepreneurs are everywhere in our communities and are a far cry from what the typical person thinks of as an entrepreneur.

Most people today when asked “who is an entrepreneur?” would respond with names like Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, or Richard Branson – multi-billionaires who are constantly in the news and operate far above the rest of us in the stratosphere of high-technology and finance. But they rarely consider their aunt who cuts hair out of her garage or their friend who started a computer repair business in a small town. It’s these real, everyday entrepreneurs who provide the best examples of how to understand what entrepreneurial thinking is really about. And critically, it is ultimately how everyday entrepreneurs think that allows them to not only survive but thrive in a VUCA world. It is in this way that understanding an entrepreneurial mindset is essential to helping people from all walks of life move towards a higher state of engagement in their work and personal well-being even if they have no interest in starting a business.

We came to deeply understand the entrepreneurial mindset through a three-pronged process. First, we interviewed hundreds of entrepreneurs looking for common ways of thinking and acting that anyone could replicate. We interviewed people like Dawn Halfaker1, a severely wounded Army veteran who founded Halfaker and Associates2 after recovering from her injuries to support her fellow soldiers still in harm’s way overseas. We interviewed Brian Scudamore3, Founder and CEO of 1-800-Got Junk4, who took a few hundred dollars and over the last 30 years turned it into a massive operation with over 200 locations in three countries. And, we interviewed Rodney Walker5 who despite a very difficult childhood in the southside of Chicago used entrepreneurial thinking to help turn around his failing high school academic record so much so that he now has degrees from Morehouse University and Yale University and is currently working on his Ph.D. at Harvard.

These interviews provided great insight into how everyday entrepreneurs look at the world and their place in it. We then dove into the psychological and sociological literature to try and explain how people like these everyday entrepreneurs can come from a very difficult situation and be successful while others who faced similar difficulties never quite live up to their potential. This research led to groundbreaking discoveries around the entrepreneurial mindset and catapulted our organization into the limelight where our work was presented to the United Nations, The European Commission, and the Pontifical Council on Peace and Justice at the Vatican6.

But how do these ideas around the entrepreneurial mindset apply to a career college or university? They apply much more than you would assume if you tend to look at entrepreneurship through a traditional lens. But the application to career education becomes very clear when entrepreneurship is looked at as a way of thinking. For instance, every school would prefer to have self-starting, growth-minded, resilient, responsible, and intrinsically motivated faculty and administrators if given the chance. And, an educational institution that can develop these traits in their students will surely earn praise from both their students and any eventual employers of their graduates.

Importantly, it is these five dimensions – self-efficacy, an internal locus of control, a growth mindset, resilience and intrinsic motivation that are the psychological outcomes of entrepreneurial experiences.

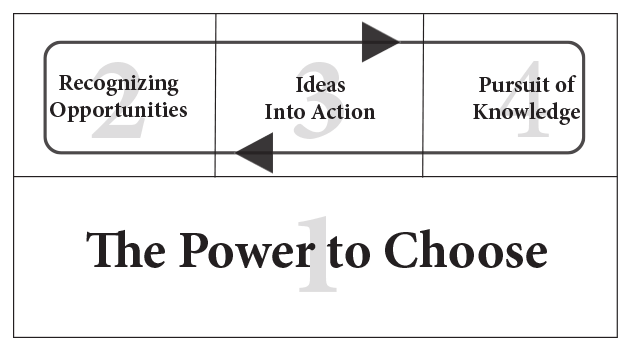

These critical skills are developed over time when individuals have the opportunity to go through what we call the opportunity discovery process of entrepreneurship. The opportunity discovery process is predicated on a problem finding and problem-solving methodology that puts the individual immediately into a situation where they begin to flex their critical-thinking, collaboration and communication muscles. Going through this experience, they learn that operating in a resource-constrained, ambiguous environment actually helps them develop the entrepreneurial skills necessary to thrive in uncertain circumstances. To get this process started there are four-phases that mimic the way that everyday entrepreneurs evaluate and pursue opportunities.

These phases begin with understanding the power of personal choice. As people experience this process, they reflect upon their own personal interests and abilities. They then form a vision for what the future could look like if there were no constraints. They eventually come to understand that ultimately their daily choices add up over time to help create their future.

Once a vision is developed it’s time to start looking outside of themselves to understand the unmet needs of others to determine problems that need solving. And problems aren’t looked at through a negative lens, but instead as opportunities for growth and possibility. Through this second phase of locating problems to solve, every unmet need of other people provides a possible path to evaluate and pursue.

Once a problem is decided upon, the third phase is entered where small actions or “micro-experiments” are attempted to find the best solution to the problem. The key here is that these small actions are not risky, nor do they cost a lot of resources. In this way risk is mitigated and large resource allocations are not required, making it much easier to continue pursuing the idea. These actions combined with stakeholder communication provide essential feedback to determine whether the solution that is being developed really solves the problem.

With this feedback from taking action in mind, phase four can be entered where new knowledge can be gained in order to assist in bettering the solution. The following diagram shows how these phases build upon each other to create an “engine” of activity. With a baseline vision of the future to be created in place, problem identification and analysis can begin, eventually leading to experimentation with solutions, which then leads to new knowledge in a continual cycle. As this cycle continues more possibilities for analysis and experimentation become apparent until the optimal solution is eventually found.

Now, let’s apply this opportunity discovery process directly into a college setting. Because individual choice is at the heart of this process it is critical that each and every employee has an opportunity to reflect on their own vision and talents. Leaders should strive to know in-depth the individual goals and aspirations of every one of their direct reports. A culture of openness and communication will need to be nurtured if it isn’t in place already to make everyone feel comfortable with discussing deeply held values and aspirations. This inward-looking evaluation of the entire teams’ strengths and individual goals lays the groundwork for moving forward toward common goals for the school. Without it, individuals won’t have had the opportunity to connect their individual vision to the vision of the organization. In the college setting once faculty have participated in this process themselves, they will see the value in creating the same environment and relationship with their students. Through this experience faculty will understand that mentoring students to develop their own vision will lead to greater student engagement and a better chance of them persisting through tough courses and life situations.

With the foundation established for the college and a clear focus on individual and collective goals, efforts can shift to the opportunity finding phase, where each and every problem that occurs creates an opportunity for someone to take the lead in solving. To make this most effective, leaders should empower their people to determine problems that need solving and pursue solutions on their own without much direction. The leader’s role should shift to one of mentorship and support versus being highly directive in nature.

At this point the real fun begins. With their newly found freedom to pursue solutions to problems that the college faces, individuals enter phase three to start testing out their ideas through small experiments and without large investments of financial resources. Once this process really gets going, some individuals will get traction with their ideas and lay the groundwork for other more tentative people to begin their own opportunity discovery process. Of course, because the entrepreneurial process is exploratory in nature many of the new ideas will fail and this is to be celebrated.

Because the cost of failure is kept low through micro-experimentation, the positive learning and individual development outcomes far outweigh any lost time or financial resources.

As ideas progress into the fourth phase new knowledge or skills that need to be developed in order to move forward with a solution become apparent. This can create an outstanding list of required professional development training for the future. Individuals will also be much more inclined to be highly engaged and learn from training that was provided through this process rather than anything that comes from a traditional top-down model. Then this virtuous cycle continues as new knowledge and understanding across the staff can lead to better problem-finding and ultimately better solutions for the college as a whole.

A culture of innovation and positive well-being for faculty, staff and students doesn’t just materialize out of thin air. It takes hard work and dedication to integrate proven principles that can help create this environment. If leaders make it a priority to develop a more entrepreneurial environment within their organizations, the first results will become apparent inside the faculty and staff with eventual positive impact on the student population. But, the steps to get to this heightened level of performance will not come easily. Institutional forces will attempt to prevent any change that makes for a more open and forward-looking institution, and they will fight hard to keep the status quo. But if they are allowed to prevail the chances of an institution thriving during uncertain times are doomed.

Entrepreneurial education has already been promoted in other parts of the world as the solution to much of what is plaguing current education systems. And, many countries around the world such as Mexico7, Denmark8, Ireland9 and South Africa10 are paying attention, and investing in entrepreneurial education for their students and institutions. As the World Economic Forum famously stated in 2009 during the last worldwide economic crisis, “Entrepreneurship education is essential for developing the human capital necessary for the society of the future. It is not enough to add entrepreneurship on the perimeter – it needs to be core to the way education operates.”11 We must strive to embed entrepreneurial thinking into the core of our educational institutions, and the methodologies described here are a great way to start.

What better time than now, during this time of great uncertainty and change to finally begin to upgrade the industrial model of education, where individual agency is completely subservient to institutional inertia, in order to create thriving, innovative institutions driven by positive change and individual well-being? Career colleges and universities can be at the forefront of this movement. But it will take brave and forward-looking leaders within these institutions to drive these ideas forward.

References:

- https://www.halfaker.com/halfaker/dawn-halfaker/

- https://www.halfaker.com/

- https://www.1800gotjunk.com/us_en/about/our_company

- https://www.1800gotjunk.com/us_en

- https://www.anewdayone.org/about

- https://elimindset.com/about/history/

- “Young Entrepreneurs, Will They Fix Mexico’s Economy?”, https://news.gallup.com/businessjournal/191189/young-entrepreneurs-fix-mexico-economy.aspx

- “Entrepreneurship Education in Denmark”, https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/downloads/entrepreneurship/Denmark_151022.pdf

- https://dbei.gov.ie/en/What-We-Do/Business-Sectoral-Initiatives/Entrepreneurship-/Entrepreneurship-Education/

- https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/380125/major-changes-coming-to-south-african-schools-including-new-subjects-and-adjusted-holidays/

- “Educating the Next Wave of Entrepreneurs, Unlocking entrepreneurial capabilities to meet the global challenges of the 21st Century”, World Economic Forum, April 2009.

ROB HERNDONas President of the Entrepreneurial Learning Initiative, oversees team efforts in all areas of company activity including product development, client support and engagement, partnership development, marketing, sales and financial decision-making. With over 21 years of experience in leadership positions as an Air Force officer along with eight years of experience in education at the university, community college and high school levels, Rob’s breadth and depth of experience is uniquely suited to expanding understanding around the entrepreneurial mindset and ELI’s groundbreaking Ice House Entrepreneurship Program.

Prior to joining ELI, Rob served as the Associate Dean of Business and Technology at Pikes Peak Community College where he participated in the implementation of the Ice House Entrepreneurship Program as a student success course as well as worked with faculty to build out entrepreneurship programming in the Business Division. His previous roles within education include leading the Air Force ROTC detachment at Utah State University where he taught the senior-level classes on leadership and national security along with mentoring over 100 students annually through their transition from college student to military officer. He also served as the Deputy Commander of the 34 Air Force ROTC detachments in the northwest region of the United States, overseeing the education of over 2,800 students and helping lead a team of 200 educators. Additionally, Rob had the honor of teaching high school math to some extraordinary students in York County, Virginia.

Prior to these positions, Rob piloted aircraft to 42 different countries and all 50 states, developed strategic budgetary plans for cyber-related programs, and led a team of engineers responsible for making modifications to a worldwide satellite control network.

Contact Information: Rob Herndon // President // Entrepreneurial Learning Initiative // 757-876-9650 // rob@elimindset.com // elimindset.com // https://twitter.com/elimindset // https://www.facebook.com/TheEntrepreneurialLearningInitiative/ // https://www.linkedin.com/company/the-entrepreneurial-learning-initiative/ // https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCera3pIEfhEaRt_AxmNyz8w

// https://www.instagram.com/elimindset/